This article was originally published February 10th, 2011 on AmosRendao.com

“Why do we fall, sir?

So that we can learn to pick ourselves up.”

— Alfred in “Batman Begins”

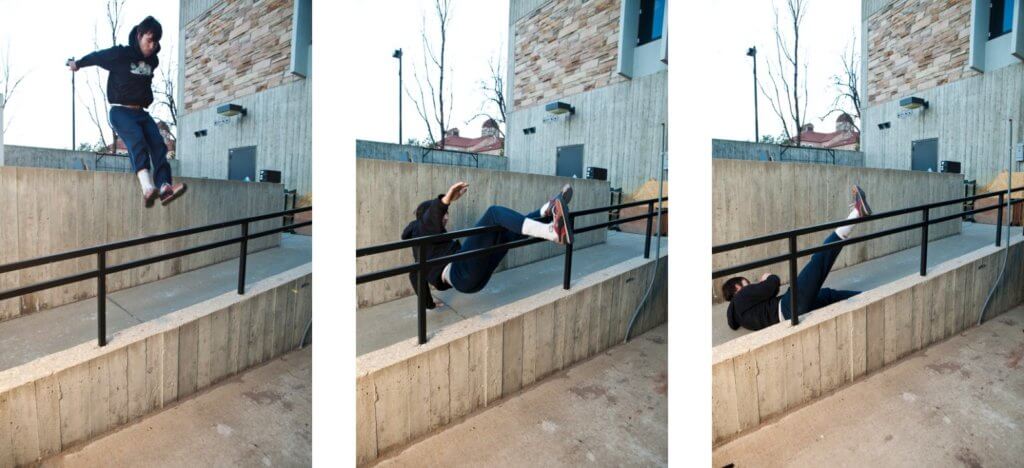

You probably get a good laugh or cringe when you see the bail marys in each issue of Jump Magazine, but your’s is coming, and bail marys aren’t just for noobs. Maybe it’s happened to you a few times already, and even then, there’s always the horizon. You will fall. No ifs, only when, and when those times come, there isn’t a chance to think, only to react.

Many people know this about the danger of falling down. For this reason, suit-clad onlookers often guess at our being as we swiftly move above them. They wonder if we have a death wish, if we’re missing part of our brains, or if we’re just simply crazy extreme sport types destined for permanent injuries.

Superimposed over our quiet landings, they are seeing the alternate realities of all the things that could have easily gone wrong. What they often don’t know is that we are prepared to react to these miscalculations like undershooting a precision at height, over rotating flips, etc. We don’t need a perfect landing, just within a certain range.

Parkour is not reserved for adrenaline addicts searching out the most creative way from point A to point Death. In comparison to soccer, snowboarding, skateboarding, martial arts, and video games, it’s the safest thing I’ve ever done. There are plenty of reasons for this, but for now, envision yourself sprinting towards a running jump. You’re now only a few steps away from take off – isn’t it nice that you don’t have to worry about some jerk slide tackling your meniscus into oblivion or your skateboard catching a barely visible pebble? Safety in parkour depends on individual body control, an ability to practice within one’s present limits, checking surfaces, and listening to one’s body. And for me, the defining element of this individual responsibility, which makes parkour safer and a sustainable practice more like a martial art, is the practice of ukemi.

The first revelation I had of the relevance and importance of ukemi in parkour was the day I attempted a fairly big (for me) Kong > rail precision > punch gainer 540 on concrete. Upon landing on the rail, one of my feet slipped out (ironically caused by stiffness due to the fear of falling), and a natural reaction was resurrected from the depths of my subconscious, muscle memory carved out through years of Aikido and Brazilian Jiu jitsu: I spread the impact of the concrete evenly along the meaty parts of the full length of my body with a break fall. A few seconds of shock wore off, and I could only laugh at how I had narrowly escaped a nasty injury.

In this particular situation, Danny Ilabaca’s philosophy “Choose not to fall” is very applicable, but no matter how positive your thinking or to what degree you can control fear and hesitation, everyone falls, including Ilabaca, David Belle, and ___________ (insert your parkour hero here).

Soon after this fall, I was also privileged to have experienced the all-time classic Kong > hands slip > knees jacked > upside down > hopefully not going for a precision on this one > yup, I was going for a precision, and it’s a huge rock…Again, muscle memory instantly kicked in. The next thing I knew, I was crouching like a ninja next to the rock that would surely have been the victor in the collision with my body. In my blurry memory of the almost-bail mary, I had helplessly watched myself manipulate a dive roll to veer off sideways, avoiding the rock and all the injuries that would have come with it. Once again, laughter, even though I was giving away my ninja crouched position to passers-by.

The many falls I’ve taken and their outcomes compel me to continue studying ukemi and adapting it to parkour, but because we aren’t dealing with just flat mats, as in a dojo, this new variation of ukemi must expand and evolve to work for our highly complex falling scenarios on concrete. As I’ve developed my own abilities, taught these concepts in our classes at APEX Movement, taught seminars on the topic around the world, and developed drills and methods, I’ve seen an overwhelming amount of success already. Whether it’s my own training, seeing those around me fall well, or hearing others tell me about how these techniques have saved them an injury or worse, I feel that ukemi isn’t just something from which the parkour community could presently benefit, it might be necessary as our discipline evolves in ways no one can presently fathom.

You will fall. And after that, you will fall again. Here are some ways that the art of falling has aided me in studying parkour:

- Falling well makes my practice even more sustainable.

- Ukemi helps me deal with fear, uncertainty, and hesitation. There are many techniques and combinations that I’m not afraid to do, not because I’m one of those freaks of nature that doesn’t experience fear, but because I know I can deal with most any outcome and fall that would resort from an unwanted slip or miscalculation on particular shapes.

- Having far less injuries ensures a strong and steady progression.

- My practice is far more enjoyable. I generally experience more laughter and fun, rather than seriousness clouded with fear.

The study of ukemi didn’t just change parkour for me, it changed my entire experience of moving, i.e. everyday life. Here are some ways:

- I have at least one epic bicycle fall a year, with a lot of small fun ones on the side. It’s an easy dive roll or side roll, but hard convincing onlookers I’m ok.

- Sometimes I trip over my own feet or an object I wasn’t aware of. Unstable rocks and ice will get the best of me from time to time.

- A few times I’ve had my feet kicked out from under me while playing soccer. Once I made it back to my feet so quickly that I was able to steal the ball from the person who stole it from me. He was a little surprised.

- Most days I encounter other ninjas in public, and in the rare event I’m thrown during an altercation, I can recover quickly and safely.

- I’ve walked away without a scratch after getting hit by a city train in Bordeaux, France (break fall on the face of the train, launched about 15 feet to an immediate dive roll once my feet touched down in order to get off the tracks before going under).

Quick note:

My friend, Jake Smith, just told me that he slipped on ice and naturally twisted away from his head-towards-ground-trajectory to get one foot under him for a graceful, almost b-twist-landing recovery. To a surprised onlooker, this may have seemed as if he casually threw a tornado kick before getting into his car. YES!

So how would this adaptation of ukemi work with parkour? Upon experimenting and being a guinea pig to a degree, I’ve started realizing that there exists a technique for every possible trajectory, velocity, direction, and orientation of the falling person to the ground, wall, rail, etc… and seamless transitions between techniques as you rotate, so that you don’t have to force an outcome but instead just react to the situation at hand. I call these falling continuums. For example, if your toes slip out on a precision and you catch the rail at your waste, you could dissipate most of the impact by continuing your momentum over the railing with a gate vault. If you were to catch a knee or foot on a kong vault and couldn’t get your feet under you, but your hips were not popped up high enough for a dive roll, the intermediary falling technique would involve reaching for the ground with one foot, not to absorb impact, but instead raise your hips as you go into the dive roll variation. In that same scenario, if your hips were popped up so high that you couldn’t dive roll, you would prepare your positioning for a break fall as you went over your head. Furthermore, if you were to have clipped your legs even harder or if you had more height in which you over rotated, the most coveted piece of this particular falling continuum would be the pulling into a flip then opening up for a soft landing on your feet. Sounds crazy, but I’ve witnessed this rarity first hand a few times. I may be alive right now because of a butt flip off of a 9 foot drop to concrete because my feet slipped out on an awkward precision…

Another falling continuum can be expressed in the idea of falling 360 degrees. Imagine a landing spot as the center point in a circle. Depending on the direction towards a feet first landing on that spot, a person could roll accordingly. From forward roll to side roll, there is a seamless transition. From side roll to back roll exists that same fluid transition, and so on, 360 degrees.

Not every piece of the falling continuum will involve a soft landing in which you laugh at your newfound invincibility, but it will always be better than the alternative of leaving your head and spine vulnerable or letting the fall stop in a small point on your body. For instance, break falls on concrete rarely feel good, but will always be better than landing on your tail bone or posting an arm out (which is just asking for breaks/dislocations).

As we move onward in this journey of parkour, we learn to embrace obstacles, and many of us stop there. Let us embrace failure, the inevitable mistakes, one of the most human things we can do: falling. Imagine our potential if we treat falling as Aikido and Judo treat it: from day one, learning how to fall correctly and focusing on correcting mistakes that must happen in our process of growth. Our injury rates will go down, we’ll further the divide between jackass extreme sports and parkour in the public mind, fear will be rare and rational. Imagine the soft gaze of a traceuse about to take on the impossible without the slightest hint of fear in her eyes. This is the path of the harmony between Ukemi and parkour. If we neglect learning how to fall well, there will always exist that nagging abyss of all the things that can go wrong that we’re not able to deal with. Instead, that intangible obstacle should be one that we train on regularly, a holistic embrace of movement with the inclusion of those inevitable things that will go wrong as we learn. If we embrace failure and falling, there is nothing left to fear, only challenges to be met and fun to be had.

If you’d like to bring Parkour Ukemi into your regular training, here are some options:

- The most effective place to start is the new ‘Art of Falling: Fundamentals‘ online training program. This course is sold out for the first round and will be available to all preorders this summer, opening again later this year. If you want to be absolutely certain you don’t miss news of it being accessible again, sign up for Parkour Ukemi updates.

- Organize a Parkour Ukemi seminar taught at your location anywhere in the world. Get in touch with me to plan something!

- Learn through free resources, examples, tutorials and other studies in the following places:

- Start training your falling technique right now with our Forward Roll tutorial below!

Written by Amos Rendao

Owner | GM | Head Coach | Pro Athlete :: APEX Movement

Founder :: ParkourEDU

Founder :: Parkour Randori

Keep up with Amos’ projects on social media:

Special thanks to Kevin Crouse, Ryan Ford, Katie Kirkwood, Ken Kao, Brendan Dudley, Pete Strayer, and Robyn Sikkema for your help, perspective, and resources.

References

1. “Aikido Dictionary.” Cardiff Aikikai. Web. 27 Jan. 2011. (http://www.cardiffaikikai.co.uk/aikido_dictionary.h